The Beatles’ In My Life still gives me goosebumps. My Mum bought me Rubber Soul when I was 17 and I remember that song stopping me in my tracks the first time I heard it. For how young, naive and inexperienced I was I could still somewhat grasp just how beautiful the reflectiveness of Lennon’s lyrics are. Today, I listen to In My Life and hear the brilliance of observation, desperation in hanging ones heart on another and, hope; hope of a man, well versed in success but still not having found whatever shall fill the hole in his soul. Incredibly mature connection and writing for someone of just 24 years old.

I recall being at a house party a year or so later with a few friends that also liked their music. I remember putting In My Life on and, about a minute in, one of the lads jumped up “fuckin’ hell Danny, I might have to slit me wrists to this one mate.” He then put Help! on! I don’t think I really considered the deeper meaning to that then but I do remember thinking (and telling the bastard!) “shown me there haven’t you pal, by changing tune to one that says ‘help me if you can I’m feeling down!’” For me that, making a sad song sound happy, which Lennon did so incredibly well, is a fantastic metaphor for clearly somewhat how he, I, and a lot of people live their lives.

It’s been over 10 years since I first read Phillip Norman’s John Lennon: The Life, which I found a brilliant in-depth insight to someone that I considered, at the time, a hero. For a lot of my life music helped me feel connected to something. I’m not at all musical myself but when I’d listen to a great song it would often feel like the artist was reaching inside me and vocalising what was going on in my head, heart and soul. If music could do that then Norman’s book obliterated me entirely. I think I cried every bastard page turn! For me, never knowing my dad, when I learned about Lennon’s father being vacant, his mother leaving her sister, Aunt Mimi, to raise him, I felt so connected. I recognised that anger, that fear, that uncertainty, that feeling of abandonment. Like Lennon, all the family that I had around me loved me fiercely but, sometimes, as a very young, very confused, scared and angry person, it’s hard to see. The song Mother encapsulates his cocktail of emotion regarding his family perfectly. A lot of those really intense feelings had left me by the time I had picked John Lennon: The Life up. Still, working my way through it, particularly the early chapters, I remember thinking, for the first time in my life, that I wasn’t the only one.

I found the work ethic of Lennon, and of all the Beatles, inspiring. One single purpose, pursued with everything that could be mustered. I finished reading Norman’s biography of Lennon in 2010 while I was in Tokyo competing at my first senior World Championships. I certainly didn’t reach anywhere near the heights of Bealtlemania but I do know what throwing myself head first into a career and challenge feels like. When I look back on Lennon’s life shortly after leaving the Beatles, although still working he had more freedom, a bit more stillness. It becomes clearer to see the results and struggles of someone with less to preoccupy him from himself, hence the increased heavy drinking and drug use, violence and regular geographicals.“One thing you can’t hide- is when you’re crippled inside.”

The morning after I competed at London 2012 I sat on my bed in the Olympic village thinking “is that it.” I couldn’t fully comprehend it then but that morning I had some realisation that becoming an Olympian, a success in my mind, hadn’t changed me. It had failed to fix me. I still woke up with myself.

I’ve not found another story more so than that of John Lennon’s that spells out the lesson that success, in whatever shape desired, does not fill the void, that only addressing the underlying stuff brings real contentment. I feel that is as valuable today, particularly for young people, bombarded by the Instagram achievement culture. The constant corrosive pictures of perfection; chiselled abs, pearly white teeth, Rolls Royce’s and swimming pools. Aside from the missing brackets in which they tell us that they take steroids, got a loan for the gnashers, rented the car and it isn’t their house, those things aren’t mending anything. That Stone Island jacket merely a plaster on a gaping wound. I often wonder, as I observe those sports people struggling when their competitive careers come to an end, whether something similar is occurring; the vehicle of preoccupation has been left yet all the original raw emotion, that created the drive to be the best in the first place, is still knocking around inside them.

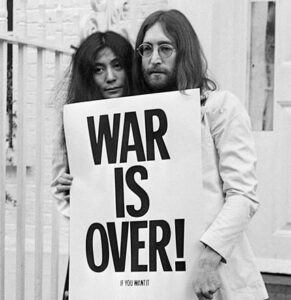

I like that John Lennon looked upon life a little differently. Only someone that does could produce an observational masterpiece like Imagine, looking wider at the human race and asking why are we living like this? Why do we subject our kids to religious dogma? Why do we kill each other? Why do some have so much while others starve to death? Why do we place material objects first? Why do we accept the made up concept of countries and borders that separates us?

It is said that only people who feel that they have experienced injustice in their own lives ask those greater questions. Feel offended by authority. Query everything. However, unlike some of his own heroes, Aleister Crowley (nicknamed The World’s Wickedest Man) and the like, I feel Lennon really did benefit humanity and helped people to make their own examinations. He pushed for peace and spoke out for more research to be done on alcohol and substance addiction, something he struggled with nearly all of his adult life. Alcohol and methadone were found in his system during his autopsy. He, to quote Biographics’ Simon Whistler “turned private pain into beauty for the world.”

I, for a few years, did turn my back on Lennon’s work, finding it to be very hypocritical. I took the youthful and naive moral high ground. Why would I want to listen to the preachings of a man who spoke of universal love and womens rights but abandoned his first family and hit his wife? A man that sang about the pain of his childhood and yet inflicted similar wounds upon his own children.

“Dad could talk about peace and love out loud to the world but he could never show it to the people who supposedly meant the most to him; his wife and son. How can you talk about peace and love and have a family in bits and pieces- no communication, adultery, divorce?” said his first son, Julian Lennon.

As time has gone on though, and as I have racked up my own list of things that I’m not proud of, I have found myself drawn back to John Lennon and his work time and time again. He teaches me that no one, no one is worthy of hero status, that there are normally always skeletons in the closet. At the same time however, real beauty and learning can be taken from people’s work and from their, sometimes unfortunately for them, very publicly known life stories.

It makes me happy to think of Lennon being in somewhat of a better place in the few years up to his untimely death. That he was able to be still for a while, to enjoy quality time with his wife and second son, Sean. I find it inspiring that he began making music again after a 5 year hiatus of, in his own words, “watching the wheels go round and round”. His final years show me that passion comes, then it goes but, if I ease my foot off the gas a little, it can and will return. “It’ll be just like starting over”

John Lennon may have passed nearly a decade before I was even born but, still, years later, when I hear his voice; I hear the rock ’n roller, I hear the activist, I hear the pain, but, most importantly, I hear hope.

“Everything will be okay in the end. If it’s not okay then it’s not the end.”