I have been upping my training each week for the last month or so, working my way back to a baseline of weekly sessions and intensity. Obviously, we are still under fairly restricting conditions due to the government guidelines for this current period but, I am happy with the steady progress I’ve been making so far.

I did have ‘a moment’ during the first week back at it though, the internal dialogue with myself, “You’re 31, why are you doing this? You don’t need to do this anymore”.

My natural approach has always been to get really stuck into everything that I do. To come at it with everything that I have. Even with filtering back in. I’ve always been resilient to/fortunate with injuries during my entire career, not really, in the grand scheme of training and competing regularly in a combat sport for my whole life, been sidelined much at all. I’d always used the fast adaptation approach with any time off that I’ve previously had, go hard and suffer for a week or two to force the body back to somewhere near where it left off. Although not intentional, I had started to somewhat employ this method on my first week back. I had said that I was gonna ease back in a bit more this time, something my coach was heavily suggesting too. However, I found myself pushing the intensity merely 3 sessions in.

Motivation is something that I’ve always possessed. My work ethic was something that, for a long time, I prided myself on. Not that for many years, I ever really saw it as ‘work’, I loved training so always wanted to do it, I never viewed it as sacrifice. That drive was just always there. As I began to get older however, late twenties onwards, I began to enjoy the days off after competitions just that little bit more. Some sessions I had to begin ‘dragging’ myself too. Dieting and losing weight to compete became harder and more mentally and emotionally taxing.

Particularly amongst older athletes, maintaining motivation becomes as important as any other area of training and preparation. Friends start earning good money, getting married, having families etc. Those things start to pull just that bit more. A few times I have also asked myself in the past, regarding the centralised system British Judo is using at the moment; even if I do really break through and get some world class results I’ll be absolutely no more financially securer than I am now (at the time), I’ll continue to receive no support, having to self fund tournaments, training camps and somehow still train full time and find time to earn a wage. What’s the point? That, “why am I still doing this?” question becoming, for periods, increasingly louder in my head.

I found those questions popping up for me mid way through that first week back. I could recognise that I was pushing a bit too hard and, regardless of intensity, that upping the training at all was going to make me more tired than I had been during lockdown. Fatigue being just a natural and unavoidable part of adaptation.

A couple of friends of mine, renowned sports psychologist, Steve Sylvester and, Arsenal FC and Reading FC legend, Brian Mcdermott are two non-Judo people that I regularly speak to about the mental side of sports training and performance. I spoke to Brian a couple of times during that first week back to structured training and relayed to him what had been going on; he spoke to me a bit about what he used to do with his older lads when he was a manager, and what he does with his own training. A simple line Brian said was about always finishing training wanting to do just that little bit more, not fully satisfying the desire to do as much as possible. Actively holding a bit back. Obviously very important for footballers that train most days and compete twice a week. I’ve always done extras; rope climbs, grip work etc after sessions. When I was younger it was like I hadn’t trained at all if I hadn’t given everything that I could in that session. Taking it easier sometimes is something that I have to practice.

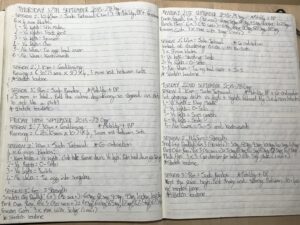

I find my training diary a very useful tool for a number of reasons. At the end of that first week back I flicked through the previous few weeks and, when I could see, right there in front of me on paper, the increase in volume of training of that last 7 days compared to the month before, I could somewhat breathe a sigh of relief. It was a gentle reminder that I had begun again and was doing the right things. I’ve been telling myself each week that ‘I am doing it’ and that is all that I have to do. I don’t need to try to set any personal bests or beast myself, just getting through the set session, what ever that looks like on that day, being enough. I’ve found myself enjoying training as much or more than I ever have before and, low and behold, have been feeling better and sharper week by week. Funny that!

I had been undecided whether I would compete again. If I continue to enjoy the process in someway like I have been then I believe that I may have a go at -81kg at some domestic events, then evaluate from there. I finished competing at -73kg last year and it has been brilliant not having to live constantly thinking about the next weight cut. Coincidently, I have noticed the results of what Victor Frankl called ‘paradoxical intention’ happening. By switching focus off something then space is there for natural improvement to occur. In my case, by not worrying about controlled diets my nutrition has been really good, considering lockdown conditions too. Habits have changed for the better.

During lockdown I took part in a webinar hosted by Paul McVeigh, former premiership and international footballer now turned psychology keynote speaker. Paul talked about “the champion mindset.” His lecture really got me thinking. I have been a good international level competitor but, although beating a few of them, haven’t really ever broken into that top group of the world’s elite. I have however, plenty of experience of being around players of that level and feel that I have a fairly decent grasp on some of the aspects that make them very good; yes, most of them love the sport, work hard, eat well, are resilient etc. At the same time as they know when to turn the heat on they also know when to turn it off, they don’t punish themselves or engage in self flagellating behaviour (that can be done with more training), they know how be kind to themselves and when and how to relax correctly. Whether they individually do this consciously or not is interesting. Some are more arrogant than others and perhaps that ‘loving themselves’ element comes into it, some are more humble and maybe they have learnt how to navigate themselves and what they do en route.

Personally, I have been my own worst enemy at times, training when I should have rested and not relaxing correctly. Regardless of my own approach I still feel that there may be something to be taken from what was discussed in McVeigh’s talk, particularly for British people practicing a Japanese sport; both cultures demanding, and often favouring, ‘hard work’ over everything else, even sometimes when working hard probably isn’t the best option.

Obviously things are different for younger athletes who may yet be lacking the foundation of years of quality training. I am aware that I, in my early thirties, am what strength and conditioning coaches call ‘a trained person,’ I’ve trained a lot my whole life, my body ‘remembers’ and it doesn’t take me long to get back to where I left off. For me, today, it’s nice just letting that process happen and not feeling obliged to force it.